Urban designer Mark Schnell reflects on Seaside’s upcoming big birthday

I’m about 18 months away from a birthday that ends in a zero. (I will politely decline to reveal the first number.) When that day comes, I’m not expecting anything earth-shattering to happen. I suspect that I will feel a lot like I did the day before my birthday, and maybe even the year before. But a milestone with a zero, or sometimes a five, will inevitably result in some reflection, and hopefully some celebration, too.

When that birthday arrives 18 months from now, I think I’ll be leaning towards the celebration side. With any luck, I will be in a far-off land with friends and family celebrating all of those decades — and getting ready to enjoy the future decades, too.

Places have birthdays, too (although we usually call them anniversaries), and we sometimes make a big deal out of those that end in zero. Like human birthdays, they are a time to reflect and celebrate.

Thankfully, there seems to be a little less anxiety about a place growing older than a person growing older. St. Augustine, Fla., which is the oldest town in the United States (or, if you want to be specific, the oldest continuously occupied settlement of European origin), will turn 456 this year. You don’t hear of anyone disparaging St. Augustine as being “over the hill” or “past its prime.”

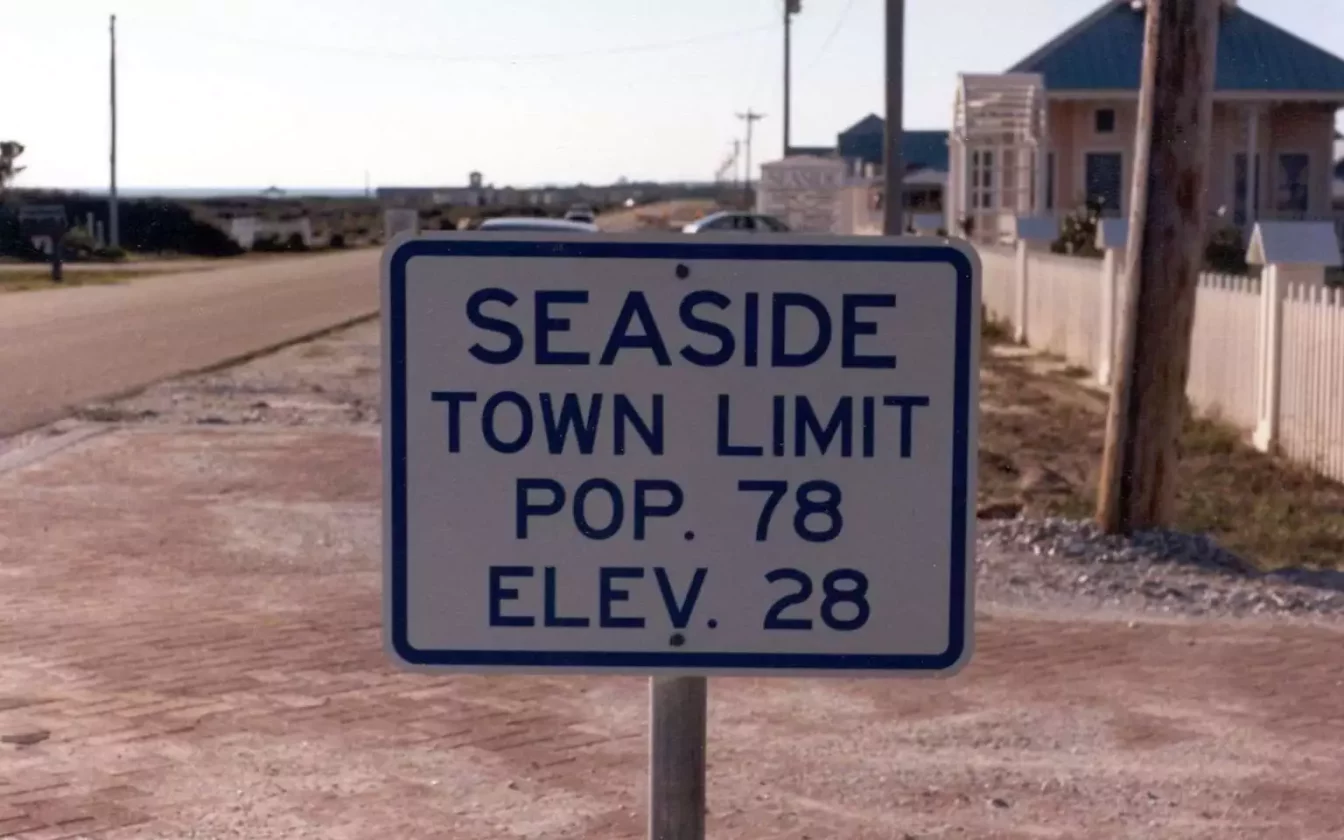

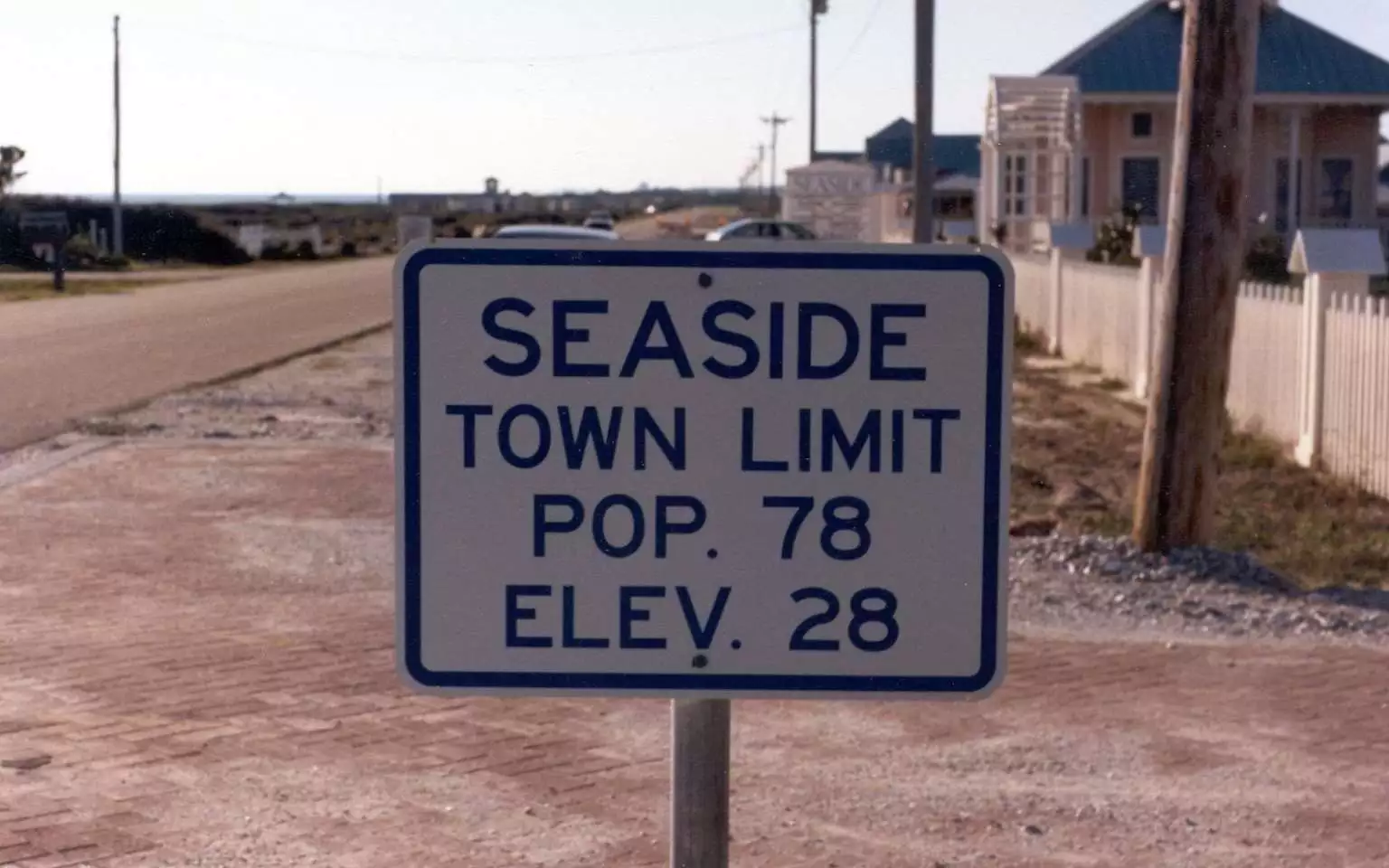

Seaside, Fla., was “born” in 1981, making this year the 40th anniversary of the town’s founding. Compared to St. Augustine, Seaside is very young. The town is even younger than I am. (Oops. That’s a clue to my upcoming birthday with a zero.) But it’s a place that’s wise beyond its years.

For readers out there who don’t know, Seaside is much more than a beautiful beach town. It’s the birthplace of an entire movement called New Urbanism, which seeks to create walkable mixed-use places rather than the development pattern known as “sprawl.” For a relatively small place of only 80 acres, and a relatively young place of only 40 years, the town has been extremely influential. This anniversary that ends in a zero is a perfect time to reflect on this legacy.

Seaside founders Robert and Daryl Davis, as well as the town’s urban designers, Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, were founders of an organization and annual gathering known as the Congress for the New Urbanism, or CNU for short. At the fourth such gathering, which took place in Charleston in 1996, a group of 266 like-minded urbanists from far and wide signed a landmark document called the Charter of the New Urbanism.

This relatively short document begins with a preamble that establishes the organization’s positions on the challenges facing communities. It begins: “The Congress for the New Urbanism views disinvestment in central cities, the spread of placeless sprawl, increasing separation by race and income, environmental deterioration, loss of agricultural lands and wilderness, and the erosion of society’s built heritage as one interrelated community-building challenge.”

That’s followed by three lists of timeless bedrock principles for creating great places, one for each urban scale: The Region: Metropolis, City, and Town, The Neighborhood, the District, and the Corridor, and The Block, the Street, and the Building.

Twenty-five years later — yes, another milestone — the document is still very relevant. Like Seaside, it’s aging very well. The entire document can be found on CNU’s web site: CNU.org.

The principles behind Seaside are clearly represented in the Charter’s principles, particularly in the latter two sections. Seaside, only 15 years old at the time of the Charter’s signing, was already influential.

One principle from the Neighborhood, District, and Corridor section states: “Neighborhoods should be compact, pedestrian friendly, and mixed-use.” This was basically a lost art for the 50 years preceding Seaside. The town reminded the world that we can still create these kind of places.

Another one provides more detail on that idea: “Many activities of daily living should occur within walking distance, allowing independence to those who do not drive, especially the elderly and the young. Interconnected networks of streets should be designed to encourage walking, reduce the number and length of automobile trips, and conserve energy.” Seaside features all of this. The town center, with its mix of shops, restaurants, offices, residences, and an amphitheater, is only a five-minute walk from the edge of town. The community includes a middle school. It’s a place where the elderly and young feel free. (Children who enjoy the walkable and bikeable streets of Seaside have been described as “free range children.”) Once one arrives in Seaside, there’s not much need for a car, which is not only a joy, but it also helps our planet.

In the final section dealing with the Block, Street, and Building, the principles deal with slightly more fine-grained details. One states: “A primary task of all urban architecture and landscape design is the physical definition of streets and public spaces as places of shared use.” Seaside’s buildings and landscapes create distinct spaces. One only needs to step into the amphitheater, Ruskin Place, or the Lyceum — or any street, really — to feel the difference when buildings and trees define those spaces.

Yet another one: “In the contemporary metropolis, development must adequately accommodate automobiles. It should do so in ways that respect the pedestrian and the form of public space.” Far from being anti-automobile, Seaside simply seeks to even the playing field between pedestrian, cyclists and automobiles.

And finally: “Architecture and landscape design should grow from local climate, topography, history, and building practice.” Seaside’s architecture reflects the longstanding building traditions of the northern Gulf coast: big porches, deep roof overhangs, elevated first stories, and more. The landscape for most of Seaside consists of native plants, which not only thrive in this climate and sand, but are some of the most beautiful aspects of the place. This is all generated by Seaside’s highly influential and often imitated code.

Those are just a few of the connections between Seaside and the Charter. How does your community reflect the principles of the Charter? If it doesn’t reflect those principles, you might have some work to do in order to improve your community. We may all be getting older (me, you, Seaside, and the Charter), but that doesn’t mean we can’t keep improving.

While I’m not entirely looking forward to that upcoming birthday that ends in a zero, I’m enjoying Seaside’s 40th anniversary. The town just keeps getting better with age.

Mark Schnell is an urban designer based in Seagrove Beach. Among his most prominent projects are three New Urban beach communities on the Texas coast: Cinnamon Shore, Palmilla Beach, and Sunflower Beach. Learn more about his firm Schnell Urban Design at SchnellUrbanDesign.com.